| Consumer Metrics Institute News Feed Subscribe to Consumer Metrics Institute News by Email |

Consumer Metrics Institute

Home of Daily Consumer Leading Indicators

| Consumer Metrics InstituteHome of Daily Consumer Leading Indicators |

| Home | History | Automotive | Entertainment | Financial | Health | Household | Housing | Recreation | Retail | Technology | Travel | FAQs | Downloads | Membership | Contact | About |

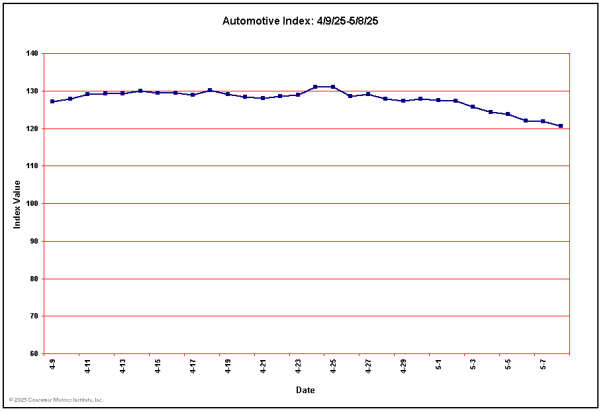

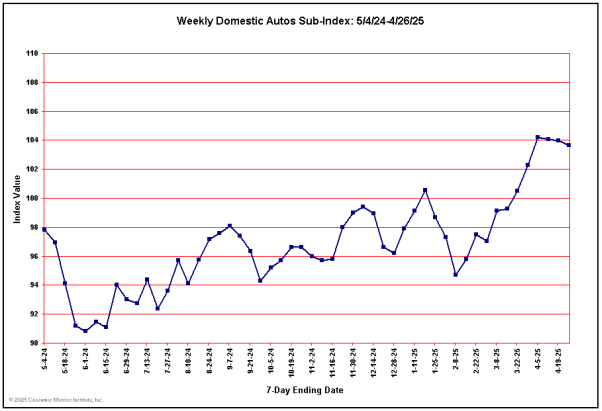

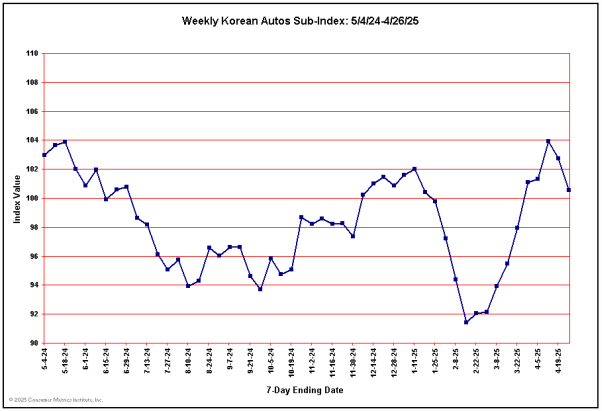

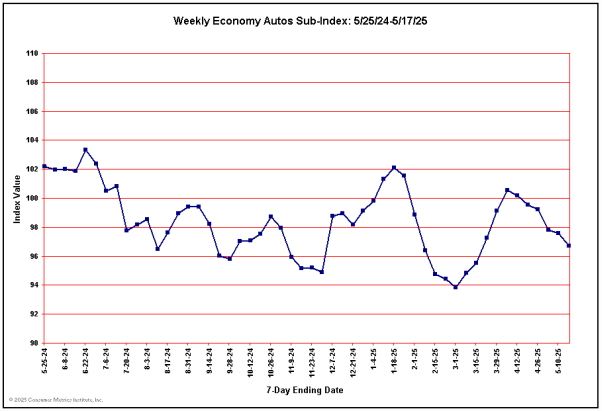

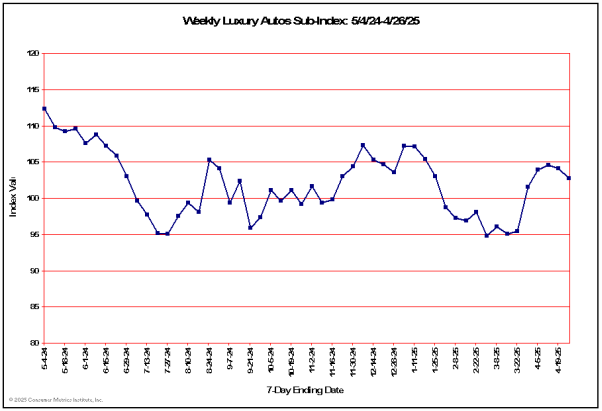

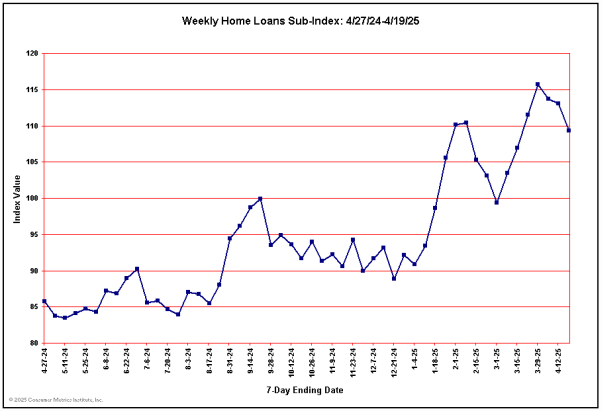

| April 5, 2011 - Automotive Euphoria; Sovereign Debt End-Games: We have been watching several mixed signals among our charts, including those in the Automotive Sector that have been commonly cited as examples of the "recovering" economy. That sector had certainly shown strength in our data until the past few weeks:  The Domestic Autos Sub-Sector had been particularly encouraging throughout the last half of 2010 and the first quarter of 2011, with year-over-year growth hovering in the single digit percentages until very recently:  But even the Korean Autos Sub-Index has begun to return to earth, dropping to what is (for it) a modest 15% year-over-year gain:  Economy Autos as a whole have traced out a pattern similar to that shown in the Korean chart above, only shifted down by between 20% and 35%:  And although the Luxury brands appear to have had a much choppier recent history, the scale of their excursions above or below the nominal zero-change 100 baseline have actually been fairly modest:  All of this is interesting in light of the resumed contraction of the Federal Reserve's measurements of consumer revolving credit and the continuing lack of consumer enthusiasm for new mortgages:  Automobiles represent a complex situation for most American families, with a number of characteristics that are unlike most other "discretionary" durable goods: ► They are discretionary only up to the point that they provide essential transportation. It is easier to have a gainful career in most of the country with at least some form of automotive transport. ► They wear out far faster than a home or most major appliances (the average American will own 10-12 autos during their lifetime). ► They are a major source of peer status and/or personal self-esteem, all of which is deeply embedded in the American culture. ► Newer models offer opportunities to cut operating costs, fuel consumption and environmental impacts. And lastly, an item we had previously overlooked: ► They are a way to rehabilitate damaged credit histories -- car loans are still there even when other loan offers have dried up. Our conclusion: even as households continue to deleverage it is probable that auto sales will fare better than most other classes of "discretionary" durable goods. Sovereign Debt End-Games - The Historical Perspective For at least a couple of decades the U.S. government and central bank have pursued policies that minimize pain over the short term while deferring the fiscal consequences to some unspecified later date. Meanwhile, the citizenry behaved much like the family of an addict: everybody knew exactly what was happening, while still looking away. Debt has always been addictive in every sense of the word; and public debt is no exception -- it is merely the clinically prescribed (i.e., Keynesian) version of the same drug that in prior centuries led hopelessly indebted individuals to prison. Unfortunately we can't just re-invent a Dickensian debtor's prison for the U.S., Japanese or Irish treasuries -- appealing as that thought might be. So, one might ask: what are the possible 21st century end-games for hopeless governmental debts? A short list would include the following (in descending order of comfort); ► Strong economic growth with managed inflation, effectively reducing the debt/GDP ratio to reasonable levels by expanding the denominator (the Keynesian presumed solution); ► External bailouts, austerity programs and lender haircuts (the peripheral Euro-zone solution); ► Some combination of a prolonged deflationary credit collapse, fiscal austerity, higher taxes, and abrogated entitlements (a solution that no government can long endure); ► Hyperinflation (the initial solution implemented in the Weimar Republic -- whose debt, sadly, was not denominated in Marks); ► The unthinkable. For the U.S. (and Japan) a dogmatic belief in the first option has been the pretense for ignoring the long term debt problem. But the litmus test for success of that scenario is simply the ongoing debt/GDP ratio. If there isn't an improvement in that ratio (e.g. Japan), an objective observer will eventually conclude that that option -- however desirable -- has demonstrably failed. Increased sovereign debt is economically beneficial only if it correspondingly increases sustainable national productivity (i.e., it has a positive ROI for the GDP and ultimately improves the debt/GDP ratio). Additionally, it is desirable to have the debts generate spending in channels with the highest possible fiscal multipliers. Why can't the U.S. just grow its GDP faster than its debt? Today the U.S. borrows largely to cover operating expenses, service prior debts and support otherwise unsustainable national entitlements. None of these spending priorities improve productivity in ways that ultimately help the debt/GDP ratio or multiply commerce -- even while the cost of carrying the new debt is (effectively) zero. Furthermore, the U.S. today faces demographic, cultural and social challenges that will further hamper economic growth -- challenges that include many of the same forces that created the "lost decades" in Japan. The loss of baby-boomers from the workplace (coupled with corresponding increases in healthcare and pension loads) will inevitably effect economic productivity, and an environmentally sensitive culture undoubtedly hamstrings rapid development. Additionally, socio-political hot potatoes such as immigration and Social Security impact the real debt/GDP ratio in diverse ways that the popular rhetoric fails to grasp. In a politically incorrect nut-shell: the U.S. economy has grown fastest when massive immigration, strip mines, smoke-belching factories, chemically enhanced agriculture, child labor and familial elder-care were normal and encouraged (a point that the Chinese learned well). And while we're being politically incorrect, during those same eras most U.S. financed military interventions only strengthened an economic hegemony and the resulting GDP (i.e., imperialism was not a four-letter word). The very society that gives us evolutionary pride may be now demonstrating the incredible difficulty of balancing environmental, economic and social progress (or sustainability). An aging, post-industrial, "financialized," liberal, humane and environmentally responsible society would be a society completely foreign to John Maynard Keynes -- and a poor scenario for the kind of strong economic growth necessary to painlessly resolve a crushing debt/GDP ratio. Returning to our list of end-game options, an external bailout is also not likely for an economy that represents roughly a quarter of the world's GDP (or even Japan's 10% share, for that matter). That shortens the list to slow political suicide by deflation/taxation/austerity, quick political suicide by hyperinflation, and the "unthinkable" -- an unsavory and limited menu of options. A cynic will argue that the choice between hyperinflation or deflation will actually be made and implemented by the economic and political oligarchy -- based exclusively on what benefits them the most. What the cynic and the oligarchy may have missed is that the Weimar Republic managed to try both hyperinflation and deflation/taxation/austerity to no avail before devolving into the "unthinkable" in 1933. By our definition the "unthinkable" is simply a vast transfer of wealth or power that violates the legal precedents of the previously prevailing regime or paradigm. It generally occurs when the previous paradigm is swept away by a set of "unthinkables" that are merely part and parcel of a visionary new order. History is strewn with instances of "unthinkable" solutions to sovereign debt problems. Tudor England offers some fine examples, quite apart from their sensational debasement of the currency: ► Henry Tudor, Sr., (the invading King Henry VII) had a particularly devious mind: in order to repay his debt to his French financiers, he confiscated certain estates of those nobles who fought against him at Bosworth Field. That was a time honored winner's prerogative, but he implemented it judicially on the dubious premise that the nobles who fought for King Richard III were actually traitorous to the "real" English King -- by virtue of an astounding and nasty retroactive dating his reign to before his battle with Richard commenced. When those estates proved inadequate to retire the debt, he confiscated certain estates of those nobles who had remained neutral non-combatants -- again judicially and on the premise that their behavior amounted to the equivalent of desertion. When even those funds ran out, he went so far as to confiscate certain estates of nobles who had fought beside him at Bosworth -- but only after again changing the commencement of his reign, this time back to after the battle ended, and using the judiciary to find his Bosworth allies traitorous to Richard. Although one has to admire the twisted logic, it is doubtful that any of Henry's contemporaries could have seen that coming. ► Henry Tudor, Jr., (the six wived King Henry VIII) was less devious than bold. He merely anointed himself head of the English church, and confiscated the Pope's English assets to solve his particular set of sovereign debt problems. Again, a solution utterly "unthinkable" in the early 16th century. But Tudor England doesn't have an exclusive franchise for the "unthinkable." It is instructive to understand that the U.S. has (at least) twice before launched "unthinkable" monetary or economic reforms, as a consequence of elections exactly a century apart: ► Andrew Jackson's 1832 re-election campaign featured populist attacks on a central bank "gone wild":  (Click on chart for fuller resolution) Jackson (unfortunately a racist boor who promulgated nothing short of genocide on Native Americans) was popular with the electorate because of his hatred for self-dealing elitist money-center bankers -- particularly Nicholas Biddle (President of the Second Bank of the United States, the defacto central bank). His campaign rhetoric might be re-cycled for use today if one were to substitute "Federal Reserve" and "Ben Bernanke" for "Second Bank of the United States" and "Nicholas Biddle." In the end he destroyed the U.S. central bank and changed U.S. monetary policy for the better part of a century. ► One hundred years later the 1932 election brought to office a populist president with a visionary new order (or "New Deal") that led to many previously "unthinkable" fiscal and social changes, many of which are with us today (although sadly not Glass-Steagall). Of special note is his Executive Order 6102:  (Click on chart for fuller resolution) that required U.S. citizens to surrender all their investment or monetary gold to the Federal Reserve by May 1, 1933 for $20.67 per troy ounce. Immediately thereafter, the Treasury announced that the price of gold was magically $35.00 per troy ounce, realizing in one stroke a profit that amounted to 15% of the entire U.S. debt then outstanding. But the truly "unthinkable" was far more fundamental: that through an executive order it became illegal for U.S. citizens to hold gold for investment or monetary purposes, rescinding millennia of personal property rights. The "unthinkable" has happened before, and it will certainly happen again. We hope that unbridled Keynesian growth resolves the U.S. sovereign debt challenge as painlessly as possible. But if it doesn't, we need to find a replacement for Henry, Jr.'s monasteries. | |